Motives for Defunding DART, Explained - Part 1

Why are suburban cities so hell-bent on getting that DART money?

Motives for Defunding DART, Explained - Part 1

Just why are suburban cities so hell-bent on getting that DART money?

For those who are unaware, residents of DART member cities voted in 1983 to dedicate one cent out of every dollar spent in their cities to contribute to funding DART. So in effect, these member cities only get to keep one cent of sales tax for their own funding needs. Other non-member cities get two cents for the same purposes. The remaining 6.25 cents go to the State of Texas for their own budget. The 8.25 cent sales tax maximum is codified in law, and is absolute. Only a bill passed by the legislature will be able to break that limit.

It’s been over a year since suburban DART member cities began their official offensive against DART and its funding. Legislative efforts failed earlier this year, and now four cities have come out with a resolution to hold an election to leave DART entirely. But in truth, this schism has been brewing much longer than that - there has been at least a half decade of effort fueled by a combination of ideology, decades of fiscal and developmental policy at the local level, the soaring real estate market, lack of dedicated state funding, and pressure from the state legislature in Austin.

There’s a lot to cover as the cause of this fight goes beyond the simple math of ‘DART gets paid X amount, and provides only Y level of services to my city.’ Under different circumstances, cities might not have even gotten to the point where they’re clamoring to claw back money from the transit agency. In this first part, I’ll cover the tax policy aspect.

Cutting taxes gets you elected.

No one likes paying taxes. An easy way to get elected into any office is to declare that voters are paying too much and promise to make the tax bill smaller. Texas has been at the forefront of this rhetoric, where the No-New-Revenue Operations and Maintenance (O&M) tax rate rules the discourse around property tax.

What is the No-New-Revenue O&M Tax Rate?

The No-New-Revenue O&M tax rate is the tax rate that could be adopted in the new fiscal year, to make sure the revenue generated would be the same dollar amount as the last fiscal year. The O&M budget is meant to cover most of the basics, such as road repairs, scheduled maintenance of water treatment facilities, mowing services, parks, libraries, and staffing (police, fire department, city employees), things that lets your city function as a livable area with the services and amenities you expect. This No-New-Revenue rate is published every year in the city financial plan and budget alongside the actual tax rate adopted by the city.

Texas Legislature Effects on the O&M Budget

In 2019, the Texas State Legislature passed a law limiting the city’s ability to raise O&M property tax from the previous year to 3.5%. To clarify, that is 3.5% above the dollar amount raised in the previous year. The stratospheric rise in real estate prices in DFW and all throughout Texas was a big driver for this law. Long-time residents were seeing higher taxes than ever before and took their grievances to Austin. Since politicians like getting re-elected, they responded.

There’s a problem with this method of relief - it limits the flexibility the cities have to respond to spikes in the cost of labor and materials. The 3.5% year-over-year cap is nowhere enough to cover for the cost increases we have seen in the past 5 years. This is even more acute in the construction industry. Due to supply chain constraints and labor shortages, there was a near doubling in the cost of concrete other materials, alongside huge increases in wages for skilled labor. These are all costs that go into fixing a pothole, renewing the striping of a road, and refurbishing a crumbling bridge.

I have personally heard frustrations from city leaders regarding this constraint put upon them by the State Legislature. They see the dollars and cents coming in and going out, and they know that the math isn’t mathing. The upcoming 2027 legislative session will bring renewed efforts to lower this cap. We had a preview in the 89th Legislature 2nd Special Session with Senate Bill 10. This would have capped the yearly increase to 2.5%, and an amendment in the House aimed to cut it down even further to 1%. This bill died on the House floor, not because of its damaging effects on city finances, but because it didn’t go far enough. Everyone is champing at the bit to be the tax cut champion without regard for the consequences, including Governor Abbott.

Some Cities Aren’t Helping the Issue

With the upward pressure on costs due to price increases, and the downward pressure on revenue generation from the Legislature, one would think that a forward-thinking city government would aim to cover as much costs as possible to the extent that is legally allowed so the parks stay clean, the infrastructure is maintained, and the libraries are kept open.

That isn’t what is happening some cities.

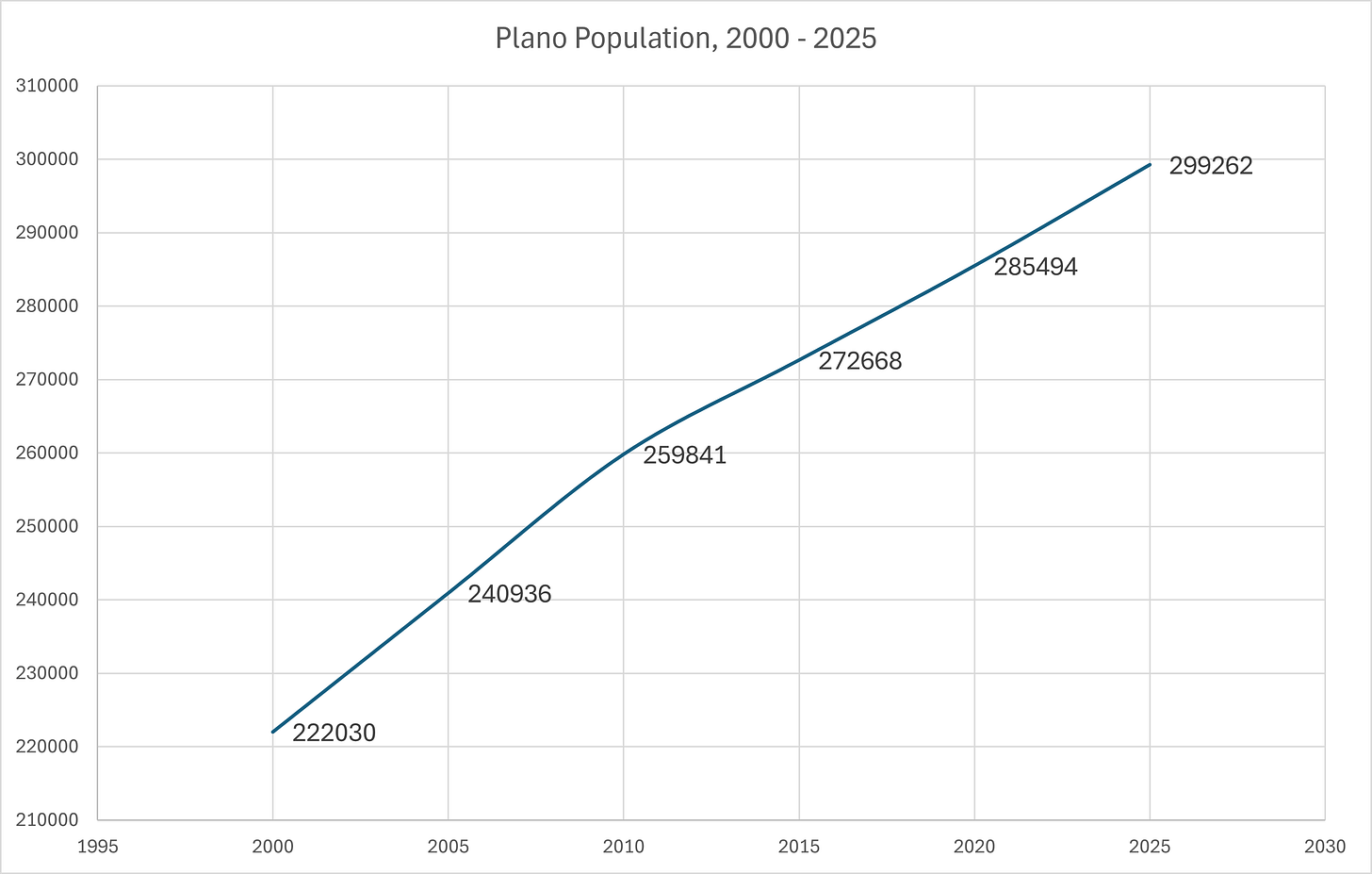

One key thing about the No-New-Revenue O&M tax rate is that it does not apply to new properties or improved properties. And suburbs have largely been beneficiaries of the population boom in North Texas, which brought new development, housing, and businesses in the past 2 decades. Some of these developments involved large cash payments from investors that cities could use to pad their budgets.

Because their budgets still balanced out, cities decided to cut their tax rate. There’s great short-term gains for doing this as long as there is space for new development. But eventually, space runs out as cities reach the limits of undeveloped land.

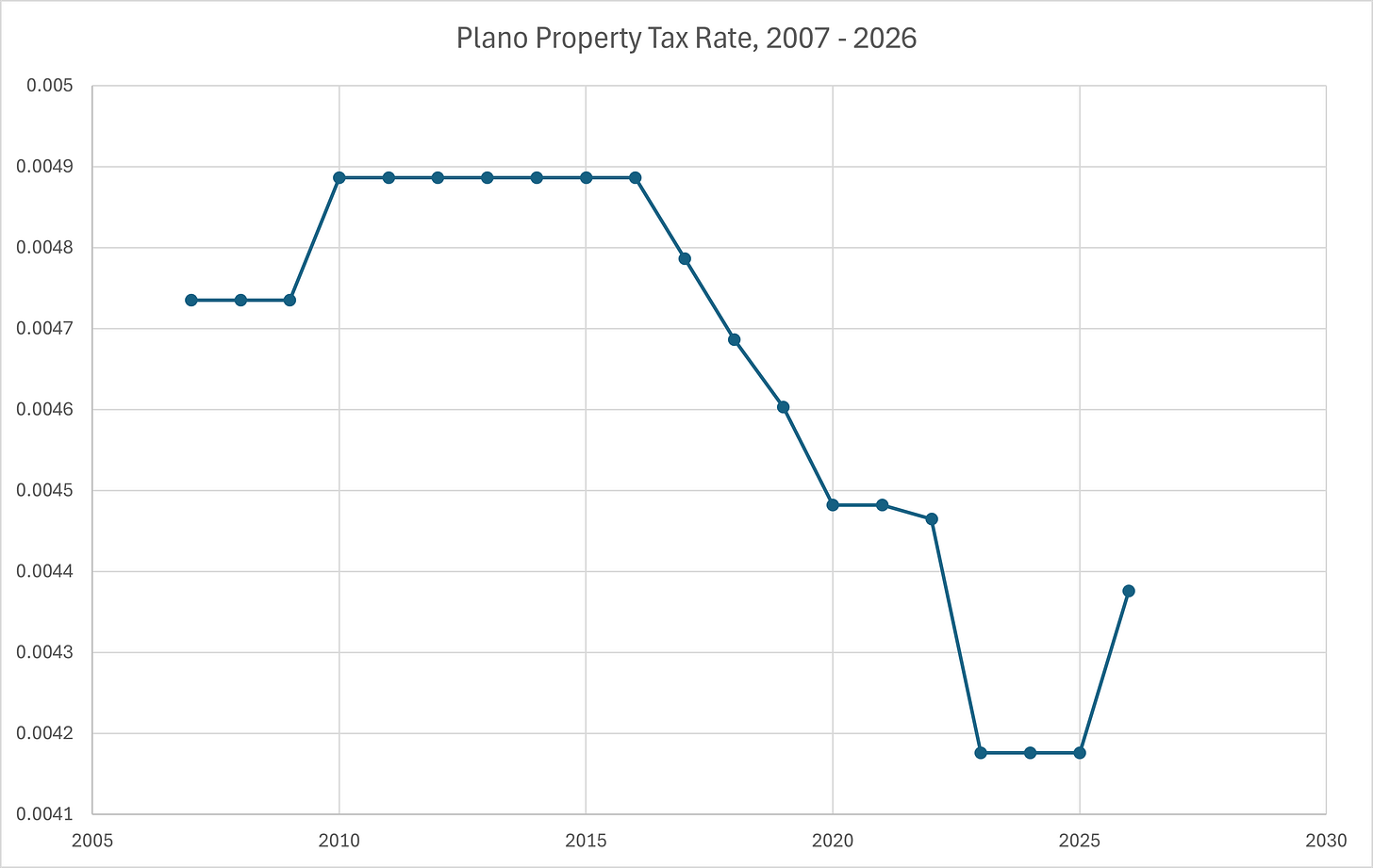

The chart above shows the historic property tax rate in the City of Plano. Plano has always had a much lower property tax rate than other DART cities excluding the Park Cities (the second lowest is Carrollton, at 0.0053875% vs Plano’s 0.004376%). From 2019 to 2023 Plano adopted the No-New-Revenue rate as their de-facto budget rate as the makeup of city council shifted to support this. Eventually, they hit the wall of unsustainability and have raised their tax rate for 2026, with some of that extra cash going to a $4 million line item for a microtransit alternative program. They even had to take out a historic bond package that included $316 million for road repairs - something that should have been handled by their annual O&M budget. There wasn’t enough money to do regular maintenance on infrastructure and the bill came due in a dramatic way.

For a broader analysis, Curtis Green has written an article that measures certain metrics that reveal the financial health of 9 DART member cities. He’s continued his work on comparing DFW cities on https://budget.city/ and continuously adding more cities. Other cities may have a better financial outlook but every taxing authority in Texas is feeling the pressure. State law is mandating the majority of city taxes to be lower than the rate of inflation. Residents expect same or better services every year. Built-out infrastructure eventually ages and requires costly repair or maintenance.

This tax policy issue is just one of the reasons why cities are eager to grab whatever money is accessible to them, and the DART 1% sales tax is a large annual sum that seems like an easy win that won’t receive much voter backlash or legislative pushback. They see state-mandated revenue cuts on the horizon and the increasingly expensive costs of running a functional city that are getting harder to pay.

Is There a Way Out of This?

As of right now, there doesn’t seem to be a politically feasible way to halt the pressure from the legislature to further reduce property tax revenue. Texas candidates in 2026 will be using it as a major policy platform. However, by leveraging and developing the public transportation options that already exist, we have an opportunity on the other side of the equation. Developing around public transportation is a proven method of increasing a city’s bang for their buck. Increasing development around train stations, transit centers, and even along bus routes will have a compounded effect that would increase property values and sales tax that would pay dividends for decades. Increased ridership resulting from these type of developments would also reduce wear and tear on the roads, as a single bus carrying dozens of people means less mileage on the roads as compared to if those individuals drove private vehicles. With reduced congestion, smaller roads would be feasible, which would mean less construction and maintenance costs per mile of road. A more focused development plan centered around public transportation would further reduce costs by concentrating city services and maintenance around a smaller area.

What To Do With That 1%?

Next week we will discuss what non-DART cities typically do with the 1% sales tax not paid to a transit agency, such as 4A and 4B Economic Development Corporations, which could provide us with insight on what the pro-pullout cities may elect to do if they get their hands on the DART sales tax.

Irving is a perfect example of the substantial ancillary benefits of DART. Regardless of the number of riders, the simple "availability" of public transportation and access nearby has attracted billions of investment and development in our Las Colinas Urban Center. Additionally, our Orange Line provides us regional connectivity.

Great article - thank you!